Ithell Colquhoun

A Visitation I 1945

© Spire Healthcare, © Noise Abatement Society, © Samaritans. The Murray Family Collection (UK and USA) / Photography Jack Elliot Evans

Ithell Colquhoun (1906–1988) combined surrealist ideas with the exploration of occult theory, creating visionary works which simultaneously looked inward to the unconscious using automatic techniques, and outward to the cosmos in her evocation of magical forces.

Colquhoun was born to British parents in Shillong, India, when the country was under colonial British rule. At a young age she left India for Britain, where she was raised in Cheltenham. She studied at the Slade School of Fine Art from 1927 to 1931 at a time when mural and decorative painting was undergoing a revival in the aftermath of the First World War. There she made large-scale narrative compositions, winning the school’s ‘Summer Composition Competition’ in 1929. On leaving the school, she continued to make large-scale paintings of mythological and biblical subject matter.

Colquhoun first encountered surrealism in Paris in 1931, and this inspired her to make other-worldly paintings of exotic plants in a style she described as ‘magic realism’. After visiting the International Surrealist Exhibition in London in summer 1936, inspired by Salvador Dalí, she began to explore surrealist methods such as the double image, where an object could be simultaneously read in two ways. Her painting Scylla 1938, in Tate’s collection, is the best-known of these, depicting both a boat sailing between two phallic rocks and the artist’s legs in a bath.

Colquhoun was a key protagonist in British surrealism, exhibiting widely in the late 1930s and 1940s, although only briefly a formal member of the British surrealist group. Perhaps her most significant contribution to surrealism was her sustained exploration of automatic techniques. Automatism had always been an important part of surrealist practice since André Breton wrote the first Surrealist Manifesto in 1924, but from 1939, together with Gordon Onslow Ford and Roberto Matta, Colquhoun explored the concept of psychological morphology, in which images begun by using unconscious processes could be worked up into finished compositions that reflected her spiritual interests. Her preferred process was decalcomania, in which a blob of paint diluted with linseed oil is applied to the surface and pressed down with a sheet of paper to produce abstract forms without the intentional use of the artist’s hand.

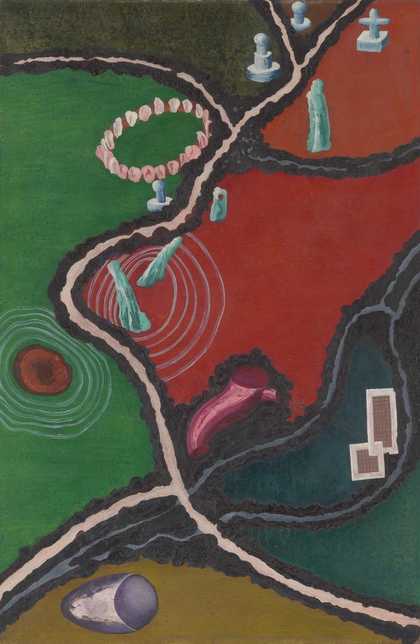

Colquhoun was inspired by the ideas of the Theosophical Society and the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, and was a member of many spiritualist and druidic societies. These influences can be seen in works exploring alchemical theories of the Divine Androgyne (a state of wholeness and integration where the masculine and feminine aspects of being are fully balanced and united) such as her Diagrams of Love series of watercolours (page 84). She also saw the landscape as a repository for mystic forces linked to female sexuality and Celtic legend. Her engagement with Cornwall from the late 1940s combined archaeological and esoteric interests. She was fascinated by the idea of places having a mystical charge and by the layers of history in the landscape, encompassing both neolithic and Christian monuments, as seen in her painting Landscape with Antiquities (Lamorna) 1950 (page 80).

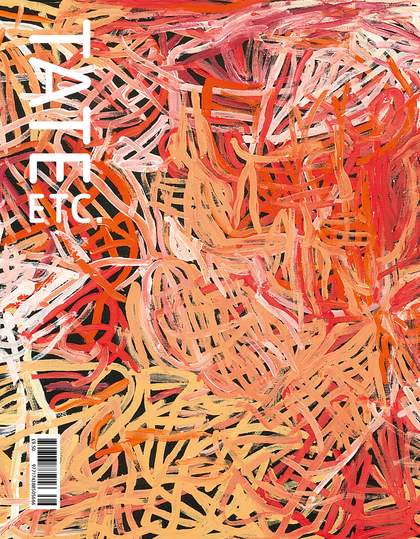

One of her last innovations in the application of automatic practices was her use of dripped enamel paint. In the 1970s she employed this in landscape paintings and in her designs for a pack of Tarot cards, which she created in 1977 (page 85). This was the first abstract Tarot deck and represents both the transcendental forces of the Tarot through pure colour and Colquhoun’s continued experimentation with medium and imagery in the final years of her career.

As the following pages show, from her arcane visions and mystical writings to her deep connection to the land, Colquhoun’s enthralling, multi-layered universe continues to find resonance with new generations of artists who seek to sense and depict the world anew.

Georg Wilson on the familiar magic of Colquhoun’s Cornish landscape painting

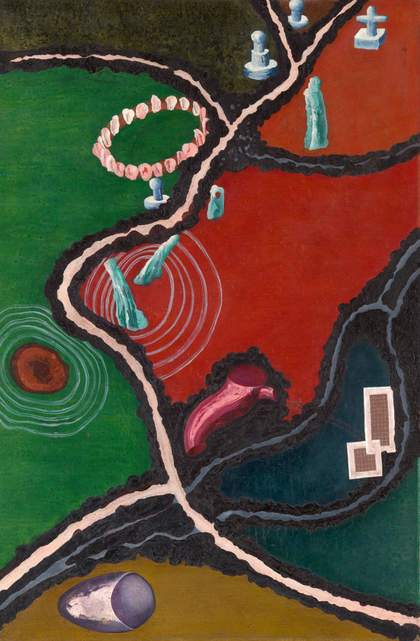

Ithell Colquhoun

Landscape with Antiquities (Lamorna) 1950

© Tate. Presented by the National Trust 2019

In Landscape With Antiquities (Lamorna) 1950, Ithell Colquhoun mapped the ancient lie of the land above the Lamorna Valley and Vow Cave, where she lived and wrote The Living Stones: Cornwall (1957). I know this place well, too. I have been visiting it since I was a child: this ‘valley of streams and moon-leaves, wet scents and all that cries with the owl’s voice’.

As a teenager I used to camp at Boleigh Farm, home to the Pipers, vast leaning standing stones, furry with lichen. The only time I’ve ever seen a wild barn owl, wheeling low over a field, was when I was 16 and sitting beneath one of the Pipers one summer at dusk.

Colquhoun paints the menhirs radiating lines of power out towards the nearby Merry Maidens, a stone circle where my mother and I have often come across damp candles and bunches of wilting flowers from some nocturnal ritual. When I was growing up, my mother showed me books on the antiquarian and esotericist John Michell, who studied this site. Then, when I began sifting through her record collection as a teenager, she introduced me to The Teardrop Explodes’ Julian Cope and his Modern Antiquarian, a guide to ancient sites that has since led us on rainy walks across the country in search of stone sisters, fiddlers, hurlers and dancers nestled among ferns and brambles.

Colquhoun’s depictions of West Penwith’s stones were usually threaded with brightly coloured networks of pulsing energy. Landscape with Antiquities is quieter. It feels less intimidating to me, more familiar. Unlike much of the valley, the fields in which the Pipers and the Maidens stand remain relatively unchanged since they were painted. You could walk along this road tomorrow using the painting as a map.

Painting is an ideal medium to transmit the significance of this land and its concealed power. Colquhoun knew this stretch of road well; she walked it often. This painting is a psychogeographic record that unveils the magic buried in the landscape. My paintings, too, reveal what is hidden to us. They are glimpses into the wild strangeness of the natural world and its unknowableness. Through paint, I can imagine a world outside of human concern and its hierarchies, where nature takes precedence.

Colquhoun’s The Living Stones ends with the final stanza from ‘Inversnaid’ (1881) by Gerard Manley Hopkins. These lines have lingered with me since I read them in Lamorna a year ago:

What would the world be, once bereft

Of wet and wildness? Let them be left,

O let them be left, wildness and wet;

Long live the weeds and the wilderness yet.

Georg Wilson is an artist who is based in London.

Sara Anstis lies with one of Colquhoun’s surreal, libidinous bodies

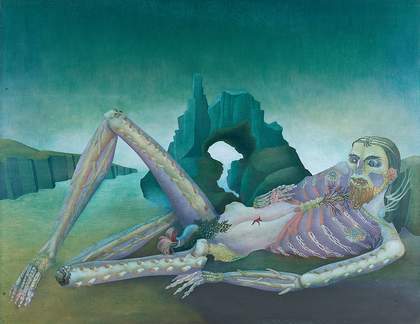

Ithell Colquhoun

Gouffres amers (méditerranée) 1939

© Spire Healthcare, © Noise Abatement Society, © Samaritans. The Hunterian Gallery, University of Glasgow

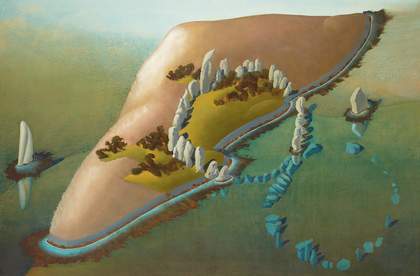

I have been thinking about Ithell Colquhoun's Gouffres amers (méditerranée) 1939 in relation to two other paintings – one created almost 400 years before it, one nearly 40 years after: Giuseppe Arcimboldo’s Water 1566 and Leonor Fini’s The Botany Lesson 1974.

All three of these pictures conjure unease while seducing the viewer with the sum of their parts. Arcimboldo’s Water is a portrait of a head in profile made up entirely of fish, crabs and other aquatic animals, their slick bodies pushing up against each other, eyes wide open, mouths gaping. Embellishing this writhing portrait is a string of pearls and a pearl earring. Fini’s The Botany Lesson depicts a naked human-like figure lecturing on the subject of a floral form suggestive of female genitalia while another figure listens. Their bodies are modelled smoothly, with emphasis placed on the curves of their musculature.

Unlike Fini, Colquhoun is not interested in depicting the figure as full or rounded. Instead, she produces craggy figures, hairy with seaweed, who double as rocks and cliffs, becoming integral parts of the landscapes they reside in. Colquhoun’s figures have a brutal physicality to them that is intensely personal to her work. In another painting, Scylla 1938, the thighs, which are the focus of the picture and double as rocky pillars, are covered with cascading, impossible folds, both flesh and rock. Looking at them, I imagine I am feasting on oysters while realising that their shells, strewn on the beach, have cut my feet to ribbons.

The libidinal energy present in The Botany Lesson and in Water is also found in Gouffres amers. The figure feels it too. See his right hand – is that not the gesture of someone feeling themselves? As a viewer, I wonder if this appeal verges on the necrophilic, as seemingly all that is left of the original figure after his ‘sea change’ – to quote from the passage in Shakespeare’s The Tempest that inspired Colquhoun’s painting – is the fauna that has eaten him. The shells, corals and anemones have held together in the outline of a human body only because their stomachs are too full to venture away just yet. These species, in their multiplicity, now stand in for the reclining nude, just as Arcimboldo’s creatures stand in for the classical head in profile.

What attracts me to this painting is its embodiment of eroticism: it contains a desire for life across species, for all of the creatures that make up the seabed and the seashore. Colquhoun is a painter who manages to see, and feel, beyond the human.

Sara Anstis is an artist based in London.

Linder has long followed in Colquhoun’s footsteps of myth and manticism

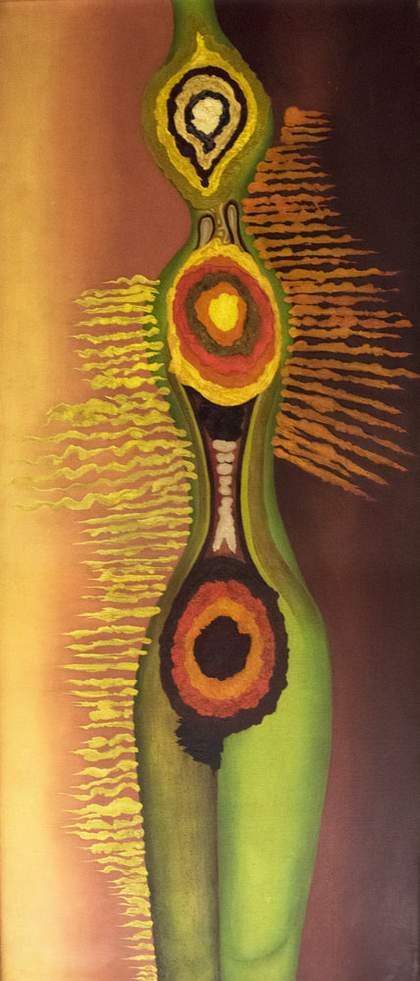

Ithell Colquhoun

Woman of Beare 1950

© Spire Healthcare, © Noise Abatement Society, © Samaritans. Private Collection. Photo courtesy Linder

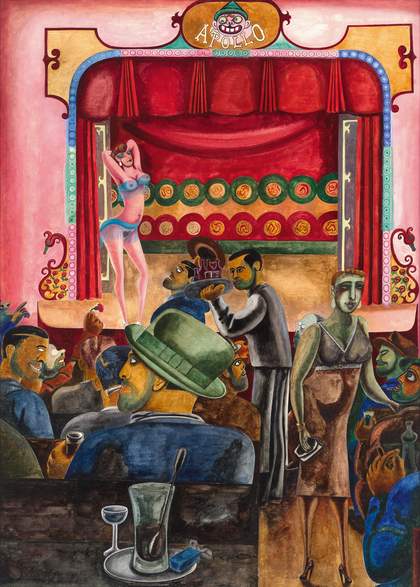

The restless child who cries out to the teacher, ‘What shall I do?’; the inhibited patient who gazes with equal blankness at the paper before him and the art therapist’s face: indeed, all who find the actual beginning of a work of art a difficulty, may be assisted by automatism.

So begins 'children of the Mantic Stain’, an essay written by Ithell Colquhoun that has been my creative pole star for the last decade – even though she published it in 1951, three years before I was born. I allow myself the conceit that Colquhoun wrote her essay specifically for my generation, preparing a primer so that she could tutor we restless children and introduce us to her mantic vision of the universe – the term ‘mantic’ relating to divination and prophecy, with a touch of divine madness thrown in for good measure.

Over the years, I have followed the path blazed by Colquhoun. Feeling her encouragement from beyond the grave, I picked up paints and let them spill mantically over the pages of 1980s naturist magazines that I’d found in a second-hand bookshop in Penzance, yards from the gallery where Colquhoun had her final solo show in 1981. In 2014, I had the very good fortune to acquire a painting by Colquhoun created using automatic techniques, Woman of Beare 1950. An art dealer in St Ives told me after I obtained the painting that Colquhoun was ‘away with the fairies’, and perhaps that much is true, for she embedded her work in Celtic myth and legend. I was familiar with the myth of this particular Irish goddess – a Cailleach or ‘Hag’ – from Colquhoun’s descriptions in her 1955 travelogue of Ireland, The Crying of the Wind: Ireland: ‘Of Beare they said / that in old age she / again became youthful, / renewing herself / like the moon; that / “her children were / tribes and races” and / that for lovers she / had heroes and gods. / She outlasted them all.’

The Crying of the Wind became a sacred handbook of sorts for me – not just for its mapping of mythic sites, but also in helping me to create an interior cartography, a somatic pathway back in time to my paternal Irish heritage. When I was a young adult in 1976, Colquhoun’s description of the Woman of Beare was never very far from my mind, even though I was reading texts such as Marina Warner’s Alone of All Her Sex (1976) while listening to bootleg recordings of the Sex Pistols. There was an anarchy of sorts happening in the UK at that time and our psyches were acutely tuned to the present moment rather than upon the past. John Lydon, the very vocal frontman of the Sex Pistols, sang: ‘You’ve got me / pretty deep baby / Can’t figure out / your watery love / I got to solve / your mystery.’

The Woman of Beare got me pretty deep, although it would be another four decades before I encountered the painting. When I did, it was love at first sight. We’ve lived together since 2015 and I study her in every light, through every season. Inevitably, she’s at her finest by moonlight when her body melts into the darkness, leaving only the slenderest of silvery contours for the optic nerve to discern. The painting’s proportions – it is just over five feet in height – allow me to stand eye to eye with the Hag, my body aligned with hers. In turn, I imagine Colquhoun standing in my position, applying oil paints to the canvas, along with what looks like parsemage, a process developed by the artist that involves the sprinkling of powdered chalk or charcoal, normally over water, but in this case lightly dusting the canvas.

In a contemporary culture presently obsessed with makeovers and rejuvenation, the Woman of Beare comes into her own: it is said that the Hag married and survived seven husbands and gave birth to myriad children, all while repeating seven cycles of youth. Colquhoun never gave birth to babies; instead she birthed paintings, drawings, travelogues, poems and more in her Vow Cave studio in Cornwall, where she spent long periods working and living alone from 1949 to 1959.

Linder is an artist who lives and works in London. A longer version of this article, ‘The Hag and the Restless Child’, appears in Ithell Colquhoun, the exhibition book published by Tate Publishing.

Lucy Stein contemplates an embodiment of the ancient magic of the land

Ithell Colquhoun

Autumnal Equinox 1949

© Spire Healthcare, © Noise Abatement Society, © Samaritans. Collection RAW (Rediscovering Art by Women). Photo: Stéphane Pons

The Living Stones changed my life by reminding me of what I had buried inside me. In the book, Ithell Colquhoun warns people not to try to initiate communications with the spirits at Harlyn Bay on Cornwall’s north coast, since there was a delicate psychic situation there. Like all landscapes that possessed her, it was the palimpsest of ancient and recent grief that drew her in.

Autumnal Equinox 1949 harnesses the particular energy of the most enchanted places in Cornwall and translates them into paint. To me, the figure is the site of the burial cists at Harlyn Bay, loaded with grave goods and skulls facing magnetic north. Or she is the stone circle Boscawen-Un viewed in late September, at dusk, through the elder tree. Her groin is the Lamorna gap, a morphological feature of the nearby coast. This body appears to have fish spines instead of human vertebrae, an atavism that suggests an exquisite consciousness that can connect with the dead and the unborn.

Ithell, born in colonial India, came to Penwith in the late 1940s. She spoke of the call of the end of the land and the phenomenon of people ‘jettisoning’ their prospects in order to settle there. The figure in Autumnal Equinox, however, is both jettisoning and radiating.

The churning psychic currents in Cornwall, and especially Penwith, perhaps unleashed by millennia of ruthless excavation and pillage of the land for its mineral contents, can make some people, usually women, feel safe. I believe that the pool of lithium that lies just beneath the earth’s crust there has something to do with this. The Cornubian batholith, a large mass of lithium-mica granite, runs beneath Dartmoor to the Scilly Isles. Certain women, including myself, just feel a little better down there.

Ithell lived on the lush side of the Penwith peninsula at Lamorna in a corrugated iron hut she called Vow Cave. ‘Vow’ or vau means cave in Cornish, so she resided within a tautology, in Cave Cave: a cave devouring a cave, a black hole. Cave houses create the conditions for magical practice.

A family friend’s mother had owned the land that Vow Cave was on and in 2015, before she died, she gave me a bunch of nick-knacks from her mother’s detritus. This is how I first came to use Ithell’s glass watercolour palettes as ash trays. These were a poignant addition to my new home in St Just, which became a social hub for friends and family. We fostered a healthily flippant attitude to the spirits of the great artists that haunt Penwith. I don’t enjoy being immersed in a nostalgic culture, and yet transference is inevitable. Objects are haunted. We are living mythology.

Lucy Stein is an artist who lives and works in London and St Just.

Bharti Kher is enchanted by Colquhoun’s uniting of spiritual and physical worlds

Ithell Colquhoun

Diagrams of Love: The Bird or the Egg 1940–1

© Tate

Sorcery and alchemy are words that rationality doesn’t much like. Luckily, art was never about knowing things for sure, nor answering impossible questions. For Colquhoun, it was about a personal and spiritual self-knowledge, and her journey was one of transformation and transmutation. It was, simultaneously, a narrowing of the distance between her body and herself: an understanding of her divine femininity. Here, art is more than mere symbol or object. It’s a shamanistic totem or an embodied spirit that shows she is open to an encounter with the spirits of colour.

Colour is energy and matter. It is received and recorded in our bodies as both memory and feeling from our subconscious and conscious. In a humanistic and holistic place, all things and all beings are connected in the outer macrocosm and the inner microcosm. Nothing at all exists that is not energy – an energy that manifests as movement between and through things.

I like to think that perhaps my work with materials is a kind of epistemology: a framework to sense and experience how materials act in relation to each other and the world. It isn’t a strict framework involving tests and analysis, however – more of a working relationship with matter and meaning. Colquhoun drawings are like this too. Her work is playful yet serious, confident yet wavering. Her writing is always asking questions.

I’m sure Carl Jung and Sigmund Freud knew of the language and sacred texts of Tantra, just as I’m sure the surrealists looked at the imagery. Colquhoun did both, I imagine, and understood that she could tap into things, perhaps higher forces, that would bring her work into being. Powers, that is, that summon all the convergences of life to paper and body, hand and mind, in the automatism that Colquhoun learnt to trust in her work as messages and codes. She had faith in the potential of what could come to be, and if there were few clear directions, no matter: she made her own, harnessing her body as her own sacred instrument, much as a hatha yogini would. I see it in the work because I feel it in the work. This is the potential art has to cross every axis – to make you feel form and colour, negation and presence. And so Colquhoun’s works become thresholds of possibility and openings of doors.

The mystics and the physicists take very different routes, yet always seem to arrive at nearly the same place: the universe, they concur, is one huge living, breathing being, interconnected, chaotic. It is everything and nothing. And we know that the human body is as complex a system as the universe. It is made up of the matter of collapsing stars. Maybe, then, all things are in the realm of making, and all objects animate. The paper and the pen have as much life as the artist. Colquhoun saw that this animism allowed freedom in the way works were made, since they potentially made themselves. I like the notion that this relates to the metaphysical belief that we are more than the sum of our parts – that, in spite of the distinctions we place on the spiritual and physical worlds, they are in fact the same.

The secrets of life are not only to be found in codes and symbols, but also simply in the act of living. Artists sometimes record these acts of living. I know that’s what I do – and that, generations before me, a woman born in India carried back to England with her the sacred, and ideas of non-dualism, and made her life the work.

Bharti Kher is an artist who lives and works between London and New Delhi. This article has been edited from ‘Tantra, Animism and Spirit’, her contribution to Ithell Colquhoun, the exhibition book published by Tate Publishing.

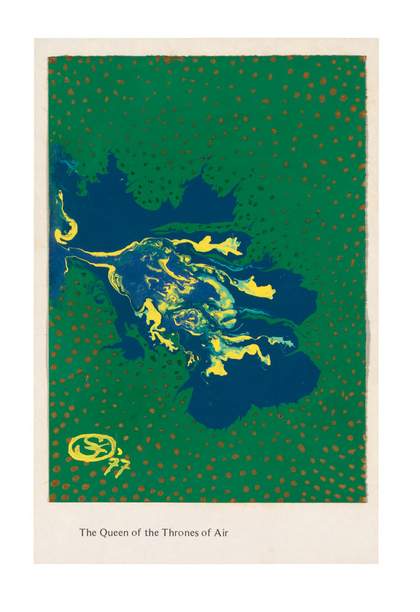

Daniella Valz Gen offers a reading from the Tarot deck created by Colquhoun

Ithell Colquhoun

Taro 1977

© Tate

Card pull:

QUEEN OF SWORDS

The Queen of the Thrones of Air PRINCE OF CUPS

The Prince of the Chariot of Waters FIVE OF CUPS

The Lord of Loss in Pleasure

At the cut:

THREE OF WANDS

The Lord of Established Strength

When I think about divination, I think of the meditative practices of wisdom keepers in various cultures throughout the ages; the ones tasked to keep their villages safe and healthy by attuning to subtle vibrations around them, keenly observing the sky, the waters or the way the fire burns.

Tools and systems of divination have evolved in cultures from these core contemplative practices, giving way to more explicit symbols. Bones, coca leaves and coffee grounds are all portable means for divining processes that are still rooted in elemental qualities and also in abstraction. Playing cards – one of my favourite divination tools – follow on and introduce sequences and characters. The Tarot expands this array of characters and symbols beyond mundane concerns to include spiritual, metaphysical and archetypal figures – and further still, in the case of the esoteric Tarot of occult traditions, adding layers of symbolic meanings of astrological and kabbalistic significance.

Ithell Colquhoun’s Taro 1977 invites the diviner into a meditative state while distilling the vast array of occult significations of the cards, which Colquhoun studied in depth, into a grouping and naming system. It brings us full circle with regards to the evolution of divinatory tools. The contemplation of colour connects us to the origin of divination, the subtle awareness of the workings of our own mind in response to the abstract forms in front of us and the undeniable emotive effect of colour on our psyche.

Upon contemplating Colquhoun’s deck for the first time, I think of breath, exhalations of colour; the process of enamel paint moving organically through the surface of paper, tinting and altering its fibres. My breath deepens and my gaze softens. Characters and sequences are still present in the cards I pull (The Queen, The Prince, The Lords) as are the elements of Air, Water and Fire, but these all become secondary to the process of finding imagery as my gaze wanders through the colours.

I see a hand in a gesture that could be seen as both asking or receiving, the reflection of the moon on water, an eye on the lunar surface, a duck’s head attached to a hollow body, mushroom spores.

Once the exercise of finding imagery appeases my overactive mind, the blue surfaces guide my gaze between the cards, puddling and pooling, tinting and subtly merging with other colours.

The reading I can distill at this time:

Breath is a dynamic, vital expression. It dictates the authority by which we handle our cognitive processes, and just as air becomes water through condensation, our emotions determine the rhythm and depth of our breath.

Emotional intelligence resides in the awareness of how feelings become a vehicle, with the knowledge that control is not the same as strength: there is wisdom and pleasure in letting movement unfold without the tension of directing it just for the sake of displaying agency. Discernment is an exercise of strength. It allows us to identify how, where, when and to what scale we should temper our breath in the awareness of its connection to our feelings and our minds.

Daniella Valz Gen is an artist, writer and Tarot practitioner based in London.